Is there life after death? Do our lives follow paths we create, or are they set out by powers beyond our reckoning? Is immortality within our grasp, and if so at what cost? These are the questions posed in The Mysterious Gentleman, which charts the career of stage magician John Nevil Maskelyne, in this, the centenary year of his death. Although the play cannot hope to provide any definitive answers, it does at least give us some insight into why we might be asking them in the first place.

The play opens at a pivotal moment in Maskelyne’s life. An engineer and amateur magician, he stages a show recreating the claimed spiritual manifestations of the Davenport Brothers. From its success he launches his own career as a stage illusionist, with the assistance of his close friend George Cooke. A touring show of the provinces leads to a 31-year stint at the Egyptian Hall on London’s Regent Street. There is a sense of Jules Verne to the first act, of two gentlemen setting out on a remarkable adventure together, but all under the silent watch of an invisible, masked figure, the mysterious gentleman of the title.

Andrew Thorn portrays Maskelyne’s complexity well, the character’s amateurism that, through his drive to bring truth and wonder to the masses, gives way to a strange optimistic naivety. His ongoing battles in the press and on stage with spiritists bring him and Dave Short’s Cooke close to ruin, and it seems only John Nevil’s assurance that there is no such thing as bad publicity that sees the pair through.

Short’s performance is charming. An avuncular foil to Maskelyne, George tempers the man’s excesses, yet allows himself to be pushed a little further into risks he would never consider alone. It is testament both to Jarek Adams script and Short’s portrayal that, when he fades from view, the moment is genuinely saddening. We share in John Nevil’s sense of loss throughout the second act.

The hole George leaves is, in the production at least, ably filled by Josh Harper, whose sensitive portrayal of Nevil, Maskelyne’s son, shows us a fragile young man lost in his own feelings of inadequacy as he attempts to take on the old man’s duties and prove himself to his father.

The play is written with a gentle wit, be it in the friendly chiding between George and Maskelyne, John Nevil’s contemplation that his lasting legacy will have more to do with public conveniences than conjury, or his delight at being described as a self-publicist. It does not shy away from its undertaking though. Maskelyne is introduced to us as a sceptic, but what drives his scepticism is a powerful desire not merely to believe in a hereafter, but to know it exists.

A career of more than fifty years is squeezed into the space of about ninety minutes, and at times it feels a little lost. Cooke and Maskelyne go from struggling would-be artists to enormously successful personalities, but that sense of success never quite seems to make itself known, save for newspaper notices and spiritualist challenges. Maskelyne’s decline, however, and his apparent descent into madness, through paranoia about losing his edge to younger magicians, and his scepticism crumbling as he approaches death, is delivered with strength and conviction.

The play is indebted to The Woman In Black, from its framing of the magic act as a rehearsal in front of an ostensibly imaginary audience, to the dark presence of the Mysterious Gentleman to whom successive generations of Maskelynes supposedly owe their success. This masked figure is present for much of the play, taking on a number of roles both benign and more sinister, before its ultimate duty.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing this production is the incorporation of a variety of magical effects. One cannot imagine a play about a stage magician without any tricks; but how best, then, to include them? Magic is no stranger to theatre, but it is most often used to bring the fantastical to life, most notably in recent years in Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson’s Ghost Stories. Here, though, we are seeing historical recreations of performance magic, and whereas small scale fare such as a disappearing pocketwatch might fit neatly into the proceedings, elsewhere there exists a tension between the play and the trick.

We are treated in the opening to a curtained cabinet illusion. George’s wrists are bound by a member of the audience and, playing the part of medium, he is placed in the cabinet. The curtain is drawn, bells are rung and silk handkerchiefs thrown through the air. This is historically authentic stuff, utilising a specific method derived from the Davenport Brothers themselves, and were it a straight performance it could have been made clear that no-one enters or leaves the cabinet once the curtains are drawn. Such proofs would no doubt disrupt the dramatic flow; the shape of the trick is different to the shape of the scene. Quite understandably the scene must come first, but we are then robbed a little of the magic.

The paradox here is that it is a theatrical production, and the suspension of disbelief when confronted with theatrical devices can be taken for granted. We do not need to see Macbeth’s dagger to believe that he sees it. In The Mysterious Gentleman a character disappears; the actor turns 180 degrees on their heel and Thorn reacts with conviction. We still see the actor, but are assured that Maskelyne does not. As theatre it is effective.

Sadly this is less true of the final effect, something that ought to be both a delicious full-stop to the play and a lasting ambiguity that we can take home with us. Yet, the ending is constructed in such a way as to break the illusion, robbing the play of what could have been its most powerful moment.

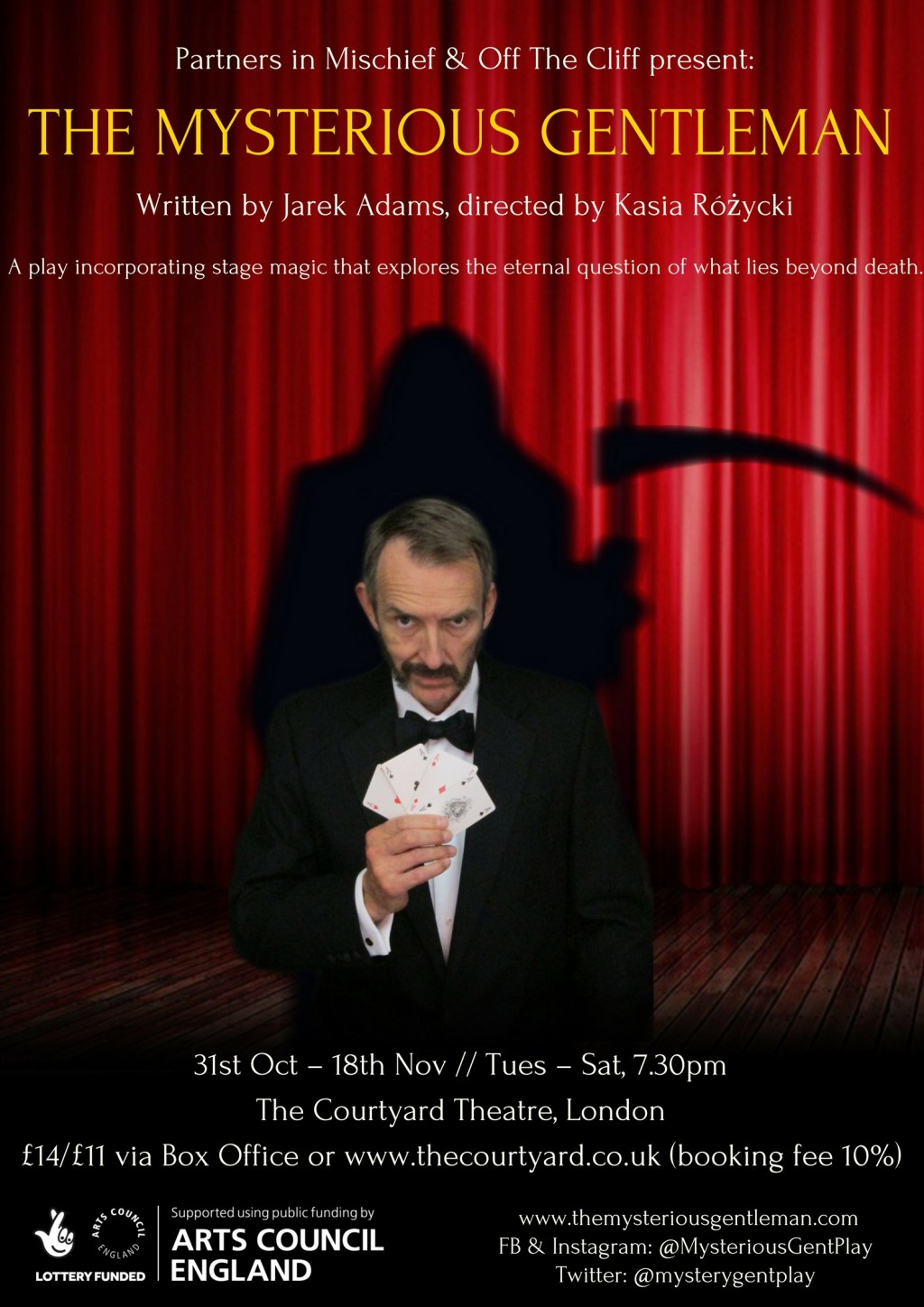

The Mysterious Gentleman is currently showing at the Courtyard Theatre till the 18th of November